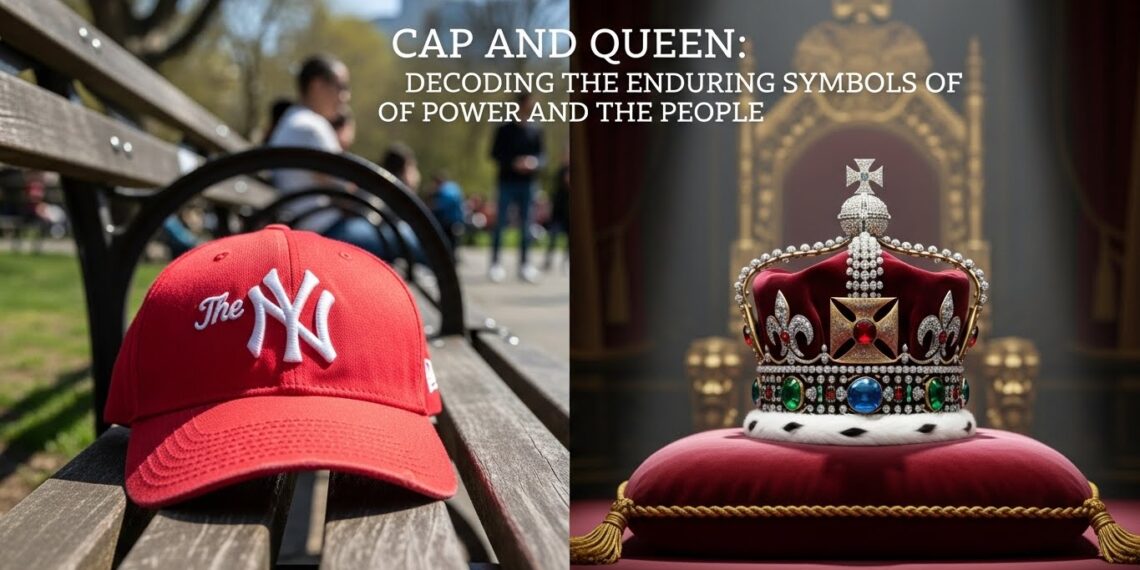

In the grand tapestry of human symbolism, few icons carry as much immediate, visceral weight as the Crown and the Cap. One glints from the heights of thrones and portraits, the other rests in the hands of the crowd or sits askew on a thinker’s head. They are not just accessories; they are potent shorthand for two fundamental, often opposing, forces in society: established sovereignty and popular will, inherited authority and earned liberty.

The Crown: The Luminary of Ordained Order

The crown is the universe contained in a circle. Crafted from precious metals and jewels, its very material speaks of wealth, scarcity, and unattainable status. Its points, whether fleurs-de-lis or crosses, reach upward, connecting the wearer to divine right, to the heavens themselves. To don a crown is to become the nexus of a realm—the living embodiment of the state, its history, and its God-given structure.

It symbolizes permanence, continuity, and the weight of tradition. It is a closed loop: power concentrated, refined, and passed along a sacred bloodline. In art and propaganda, the crown radiates light, positioning the monarch as the sun around which all life orbits. Yet, that same light can cast long shadows of oppression, representing a power that is distant, immutable, and absolute.

The Cap: The Banner of the Aspiring Spirit

Against this gilded symbol stands the cap, most powerfully in the form of the Phrygian cap or liberty cap. Of simple felt or cloth, often red, it is soft where the crown is hard, accessible where the crown is exclusive. Its origins are humble, historically worn by freed slaves in ancient Rome, making it an eternal emblem of emancipation from servitude.

During the American and French Revolutions, the liberty cap was hoisted on poles, embroidered onto flags, and worn by revolutionaries. It became the signature of the common citizen awakening to their own power. Unlike the crown’s divine authority, the cap’s power derives from the collective human spirit—it stands for self-governance, enlightenment, and rights not bestowed but claimed. It is the hat of the working thinker, the rebellious student, and the liberated people.

A Dialogue Across History

The relationship between cap and queen is not merely one of opposition; it is a continuous, gripping dialogue.

-

The Challenge: The cap, raised on a pike, is the ultimate challenge to the crown. It represents the moment the “demos” declares that authority flows upward from the people, not downward from a monarch. The French Revolution staged this drama in its rawest form.

-

The Absorption: Sometimes, the crown cleverly absorbs the symbol of the cap to maintain legitimacy. Monarchs have presented themselves as champions of the people, using populist imagery to soften their imperial power.

-

The Modern Synthesis: Today, we see a fascinating synthesis. Queen Elizabeth II, a figure of immense traditional authority, was also a master of wearing the figurative cap—projecting a sense of quiet public service and stability for her people. The modern constitutional monarchy itself is a kind of truce between the two symbols: the crown remains, but its power is capped by the democratic will of the people.

Beyond Politics: A Personal Metaphor

On a personal level, this duality plays out within us all. We each have an inner “crown”—the part that seeks recognition, authority, and mastery in our domains. And we have an inner “cap”—the drive for autonomy, freedom from external constraints, and the raw, creative spirit that questions the status quo. The balance between our need for structure (crown) and our need for liberty (cap) is a lifelong pursuit.

Conclusion:

The crown and the cap are far from relics. They persist in our logos, our political cartoons, and our subconscious. They remind us that the tension between centralized authority and individual liberty is the very engine of history. One represents the anchor of tradition, the other the sail of progress. One asks for reverence, the other for reason. In understanding these two powerful symbols, we gain a lens through which to view not only our past but also the perpetual, vital struggle to define power in our present. The story of civilization, in many ways, is the story of the cap and the queen.